Little 'a', Big Factor

There are an estimated 17.9 million people worldwide who die from cardiovascular diseases (CVD) a year.2 This represents on average 32% of all global deaths, and of those, 85% are due to heart attacks and strokes.3

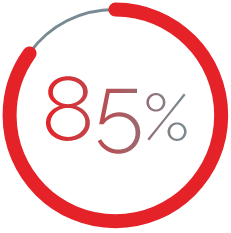

Typical distribution of Lp(a) in the general population5

Elevated Lp(a) is highly prevalent

Unlike LDL-C Levels which have a normal distribution, Lp(a) levels are skewed in most populations.5,22 Elevated Lp(a) influences atherogenicity from birth1 and Lp(a) is approximately 6-fold more atherogenic than LDL on a per particle basis10

Figure adapted from Nordestgaard BG, et al. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(23):2844–2853.

Elevated lipoprotein(a), also known as lipoprotein little a, or Lp(a), is a genetically determined condition that independently increases CVD risk.1,4 Lp(a) may be measured in nmol/L or mg/dL - generally elevated Lp(a) is classed as ≥125 nmol/L or ≥50 mg/dL.17-19 However variation of cut-offs and units exists in reported studies.17

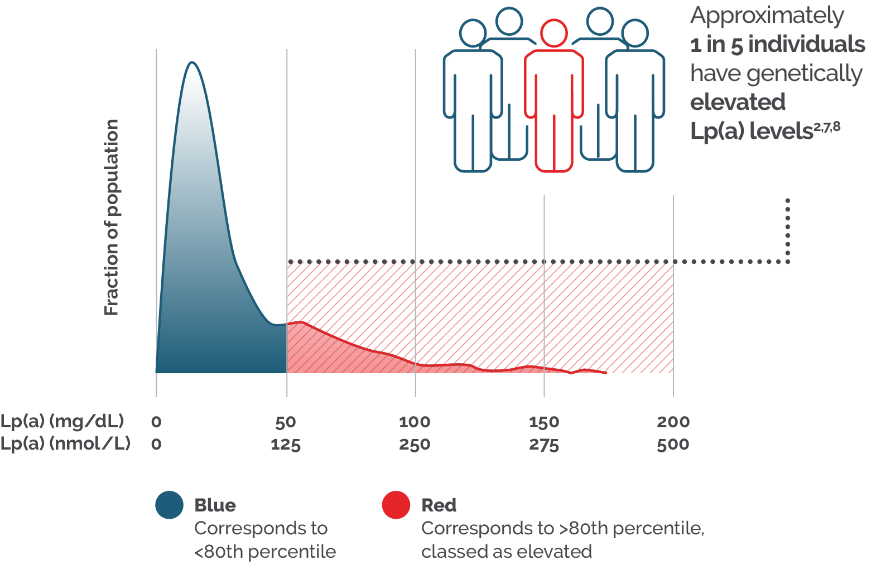

Findings from the UK Biobank show ASCVD incidence is linearly associated with Lp(a) concentration, with risk increasing continuously with increasing Lp(a) concentration.21 For example, individuals with elevated Lp(a) (>117 mg/dL) are 2.6 times more likely to experience a myocardial infarction (MI) compared to individuals with Lp(a) <5 mg/dL.6 An Lp(a) level of 100 mg/dL (~250 nmol/L) approximately doubles the risk of an atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event, irrespective of an individual’s absolute risk at baseline according to research in 2022 and 2023.5

And yet, despite 1 in 4 patients with ASCVD having elevated Lp(a) levels, it is not routinely tested in day-to-day clinical practice.26,27

The potential value of including Lp(a) testing in cardiovascular risk evaluation

Lp(a) testing is a basic, high-value* blood test, that does not require a fasting sample.4,14

Lp(a) assays reporting mass (mg/dL) or molar (nmol/L) units are reliable and enable a more complete risk assessment when taking into consideration the patient’s global CVD risk profile.15,16

An accurate risk assessment of ASCVD patients, particularly those who have already experienced a CV event, can help to reduce a patient’s risk of a subsequent event and in turn, reduce the significant burden of CVD across the NHS.11-13

Learn more about how to test your patients’ Lp(a) levels.

Lp(a) testing can improve CVD risk assessment in primary and secondary prevention settings

- One in three patients with very elevated Lp(a) levels§ were reclassified into a higher primary prevention risk category

- >50% of all patients with very elevated Lp(a) levels§ were reclassified into a higher secondary prevention risk category

SCORE: Conroy et al. Eur Heart J 2003;24:987–1003; https://www.heartscore.org/en_GB (Last accessed June 2025)

SMART: Dorresteijn et al. Heart 2013;99:866–872; https://u-prevent.com/calculators/smartScore (Last accessed June 2025);

§>99th percentile, mean Lp(a) of 460 nmol/L.

Identification of

elevated Lp(a)

There exists considerable scope to increase access to Lp(a) testing as part of routine cholesterol checks. Lp(a) should be routinely measured at least once in all adults† as it may benefit patients with CVD. It is particularly informative in:

- Recent events where hospitalisation represents a convenient opportunity to assess Lp(a)-driven CVD risk;15

- Recurrent events (including recent ACS) as patients with elevated Lp(a) have a higher likelihood of suffering recurrent CV events and;22

- Premature events‡ as elevated Lp(a) is an important contributor to premature CVD.23

This could help healthcare professionals (HCPs) better understand their patients’ overall CVD risk, inform treatment intensification and management of global CVD risk factors, as well as identify a potential underlying genetic cause of CVD risk.24,25

Testing Lp(a) in your patients with CVD could help to accurately assess their risk of having another event, allowing appropriate and timely interventions to take place to help improve patient outcomes.11-13

There is growing evidence highlighting the significant role of elevated Lp(a) in the development of ASCVD. HEART UK have therefore published a consensus statement providing guidance on managing elevated Lp(a) and urging action.28

Footnotes:

*High value” not only supports potential cost-effectiveness of Lp(a) testing, but also the direct benefits of Lp(a) testing to patients, e.g., patients with an Lp(a) measurement are more likely to have initiated treatment with lipid-lowering therapies to manage global CVD risk.

† Includes youth with: 1. Clinically suspected or genetically confirmed FH; 2. Ischemic stroke of unknown cause; 3. First-degree relatives with a history of premature ASCVD (age <55 years in men, <65 years in women); 4. First-degree relatives with elevated Lp(a).

‡ Consult local guidelines for the definition of premature.

References:

- Enas EA, et al. Indian Heart J. 2019 Mar-Apr;71(2):99-112.

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1 [Last Accessed July 2025]

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) [Last accessed July 2025]

- Reyes-Soffer et al. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2022;42:e48–e60.

- Kronenberg, et al. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(39):3925–3946.

- Kamstrup PR et al. JAMA. 2009;301(22):2331–2339.

- Tsimikas & Marcovina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(9):934–946;

- Nordestgaard BG, et al. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(23):2844–2853.

- Afshar M, et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(12):2421–2423.

- Björnson E et al., J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024: 83(3):385-395.

- Verbeek et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69 (11): 1513-1515.

- Wesorick et al. The American Journal of Medicine (2005) 118, 1413.e1-1413.e9.

- Mach et al. Eur Soc of Cardiol. 41: 111-188. 2020.

- Nordestgaard BG. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(13):1637–1646.

- Szarek M, et al. Circulation. 2023;doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.066398.

- Kronenberg F, et al. Atherosclerosis. 2023;374:107–120.

- Wilson DP, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2019;13(3):374–392.

- Grundy SM, et al. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1082–e1143.

- Kronenberg F. Atherosclerosis. 2022;349:123–135..

- Cegla J, et al. Atherosclerosis. 2019. 291:62-70.

- Patel AP, et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41(1):465‒474.

- Tsimikas S. A Test in Context: Lipoprotein(a): Diagnosis, Prognosis, Controversies, and Emerging Therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(6):692–711. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.042.

- Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2518–2528. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0902604.

- Koschinsky ML, et al. Lipoprotein(a): insights from recent epidemiologic, genetic, and therapeutic studies. J Clin Lipidol. 2024;18(2):e308–e319.

- Willeit P et al., Baseline and on-statin treatment lipoprotein(a) levels for prediction of cardiovascular events: individual patient-data meta-analysis of statin outcome trials. Lancet. 2018 Oct 13;392(10155):1311-1320. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31652-0. Epub 2018 Oct 4. PMID: 30293769.

- Nissen SE, et al. Open Heart. 2022;9(2):e002060

- Byrne H, et al. 2025 EAS Congress (https://www.medicalcongressposters.com/FileUpload/QRPDF/How%20common%20is%20elevated.pdf)

- Lp(a) Taskforce. A call to action from the Lipoprotein(a) Taskforce. Available from: https://www.heartuk.org.uk/downloads/health-professionals/a-call-to-action-from-the-lipoprotein(a)-taskforce---august-2023.pdf (Accessed July 2025)

UK | July 2025 | FA-11414778